History: Inside the Villa-Zapata Summit

Villa and Zapata had met in Xochimilco, then a village in the outskirts of Mexico City.

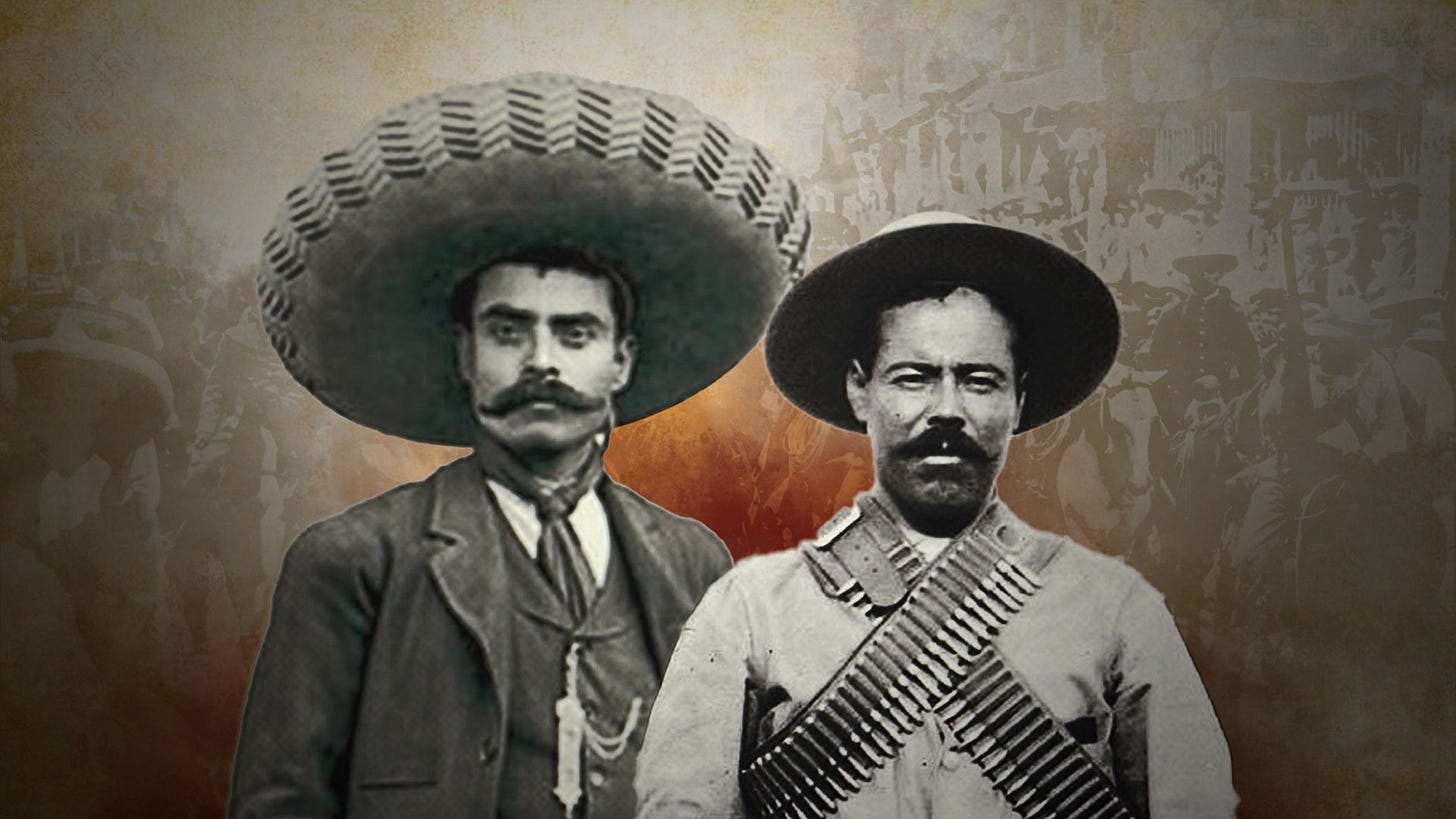

Some photographs transcend mere documentation; they become visual metaphors of shifts in history. Lincoln at Gettysburg, Lenin addressing the masses in Petrograd, the man in front of the tank in Tiananmen. These are not just images but emblems.

For Mexico, one image stands above all: the (only) meeting of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata in Mexico City, …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Daily Chela to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.