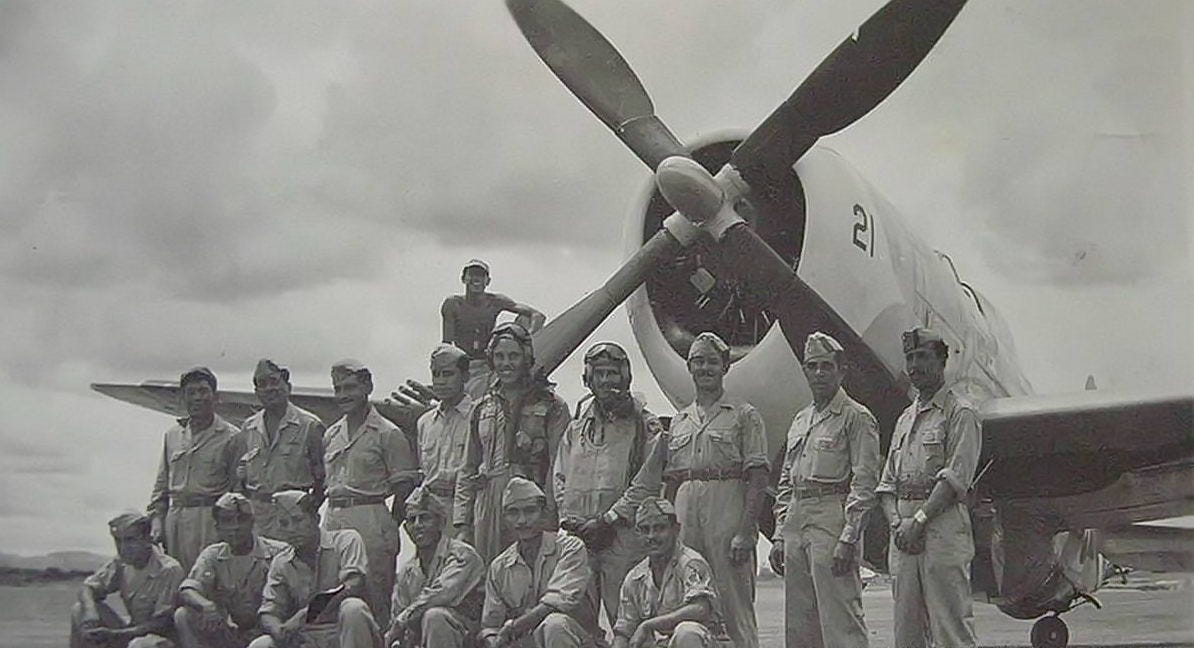

The 201st Squadron: Mexico’s Greatest Generation

The Mexicans did not fight Nazi Germany or Italian fascism, but Japanese imperialism in Luzon and Formosa

Historians agree that Mexico’s main contribution to World War II was to provide the United States with precious raw materials especially oil—sorely needed in the war front across the ocean. But few know that Mexico, in addition to Brazil, was the only country in Latin America to send troops against the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo Axis.

This is the story of the 201…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Daily Chela to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.