The Battle Of Los Angeles

A weekly newsletter dedicated to Mexican American news, politics, and commentary.

DAILY CHELA LINKS

“Do not look with jealousy upon the hardy pioneers who scale our mountains and cultivate our unoccupied plains,” wrote Mexican general Mariano Vallejo in 1846, referring to the American migrants arriving in California in search of fortune. “Welcome them as brothers who come to share with us a common destiny.”

The history of the American West is filled with declarations and promises that time has rendered steeped in irony. A few years earlier, a French attaché stationed in San Diego had written that “whatever nation chooses to send there a man-of-war and 200 men” could take California.

Claiming the West

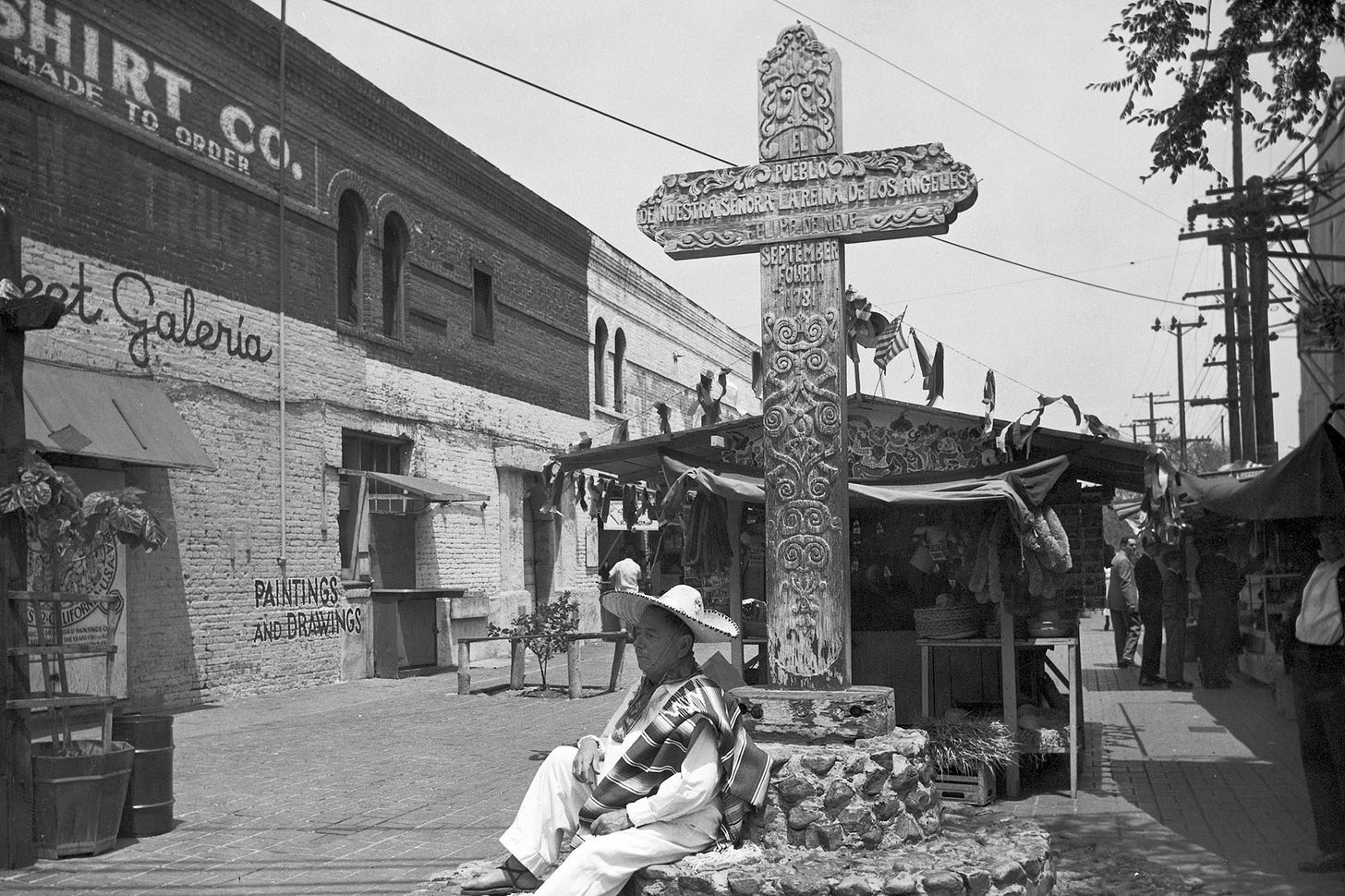

By the mid-19th century, “el pueblo de Los Ángeles” was California’s only significant settlement, home to about two thousand Mexican inhabitants. Surrounding the town, in bountiful villages and farms, lived more than ten thousand others, alongside settlers from various nationalities—people we would readily call immigrants today. The Sacramento Valley was home to several hundred Americans.

From its inception, the United States had displayed a voracious appetite for territorial expansion, and by 1845 its gaze was fixed on the Pacific. That year, Commodore John D. Sloat was instructed to occupy the port of San Francisco and await further orders to extend control across California. Those orders came one year later.

The main strategic points—Monterey, San Diego, Santa Barbara, Yerba Buena—fell without resistance. Some of it was surprise, some resignation from the native population. Mexico City was distant, and what little arrived from the capital came in the form of taxes, not aid.

An Occupation Without Glory

Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of California, a Santa Claus-like figure, attempted unsuccessfully to organize a resistance. He could do little more than watch as American forces occupied one town after another without firing a shot. U.S. Marine Robert F. Stockton announced California’s annexation and promised protection for both Mexicans and foreigners. By August 1846, the American flag flew over every port, and the local Mexican population had begrudgingly accepted the new order.

But the calm did not last.

Less than forty days later, on September 23, the rebellion of Los Angeles erupted—the first major act of resistance by a Mexican population under U.S. occupation. According to one Mexican source, the insurrection arose from the “patriotic fire which burned in the hearts of the majority.” But there were also more tangible causes: “the despotic conduct of military authorities, police regulations”, and the tyrannical behavior of Governor Archibald Gillespie.

Even General Stephen Kearny, remembered for the conquest of New Mexico and California, admitted bluntly that the Mexicans had “been most cruelly and shamefully abused by our own people,” adding: “had they not resisted, they would have been unworthy of the names of men.”

The Battle of Los Angeles

The spark was struck when a local resident surnamed Varela attacked the American garrison. Though repelled, his act of defiance inspired others. The next day, Captain José María Flores gathered more than 500 armed residents and camped on the outskirts of the city to prepare a full siege. On September 25, the encirclement of Los Angeles began. By the 30th, Gillespie raised the white flag. He was allowed to withdraw with his men—but, crucially, also with their weapons and ammunition. The Mexicans believed the matter settled.

They were wrong.

A week later, reinforcements arrived: U.S. marines and sailors, accompanied by Gillespie himself, marched back toward Los Angeles seeking revenge. Along the way, they encountered a Mexican cavalry unit, which defeated them once again. Elated, the locals reestablished the regional congress and appointed Flores governor of a city that, for a few months more, returned to Mexican hands.

The Final Counterattack

By December, however, the arrival of a larger U.S. force under General Kearny—and the formal outbreak of war between Mexico and the United States—rendered the Mexican position untenable. In January 1847, near the indigenous village of San Pasqual, a brutal hand-to-hand battle unfolded. More bloody clashes followed at the mission of San Juan Capistrano and, ultimately, on the banks of the San Gabriel River—locations that still bear their original names in the Los Angeles area. Mexican defeat was inevitable.

The last insurgents retreated toward what is now Pasadena. On January 10, 1847, the Stars and Stripes once again flew over the still existing central plaza, and Kearny ordered the construction of a military fort. One American captain recorded in his diary:

“A flag of truce … was brought. They proposed… to surrender the City of Los Angeles, provided we would respect property and persons… we moved into the town… expecting an attack. The streets were full of desperate and drunken fellows who brandished their arms and saluted us with every term of reproach.”

Cahuenga: End of the Battle, Start of the Deal

The lesson was clear: while the Mexican population had initially welcomed the Americans in a spirit of shared progress—and later accepted occupation as an inevitability—it could not tolerate the injustice and abuse meted out by the new rulers of the land.

And so, on January 13, the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed. It established something that history seems to put in front of us now: that Mexicans—including the rebels—could remain in the country, protected in their persons and property, and granted the same rights as American citizens. Stockton, initially reluctant, accepted the terms, recognizing they were the only viable path to peace and reconciliation.

The Treaty of Cahuenga ended the hostilities and marked the beginning of the new order. On the Mexican side, three representatives signed the accord, including a name familiar to every Angeleno today: Agustín Olvera, whose name lives on in the city’s most iconic street.

“This was the last exertion made by the sons of California,” one Mexican source would later write, referring to the protesters. They “more than once, taught the invaders what a people can do when fighting in defense of their rights.” ✔

Gustavo Vazquez-Lozano,

Contributing writer.

WILL YOU HELP SUPPORT INDEPENDENT MEDIA?

At The Daily Chela, we believe that every story matters and that diverse perspectives are crucial in shaping a more informed community. Our mission is to provide a platform for Chicano and Latino voices, share vital stories from our community, and cover news with the depth and context it deserves.

But we can’t do this without you. Independent media relies on the support of people like you to continue our work. Your subscription is not just a donation—it’s an investment in the future of informed, diverse, and truthful journalism.

Here’s how you can help:

Make a Monthly Contribution of only $5.99: Your financial support will help us cover operational costs, pay our dedicated team, and expand our reach to more readers.

To subscribe or donate, simply click on the “upgrade to paid” button. If you have any questions or need more information, feel free to contact us.

Thank you for your support and for believing in the power of independent media. We have come a long ways this past year. Together, we can make sure that every voice is heard and every story is told.