Why Chicanos Reject “Latinx”

Special interests want us to forget our history. They want us to believe we can all be summed up with one generic label.

JOIN TODAY and get 10% off your Daily Chela Insider subscription for an entire year.

It takes an impressive level of hubris for a journalist to call their own readers “Latinx” when knowing so many of them despise the label. At the very least, it demands a level of willful ignorance that can only be explained by an elitist political worldview or weirdly insular social circle.

Proponents, of course, love to boast that they are being “inclusive.” But to the average person whose entire world doesn’t revolve around projecting fake virtue on social media, the argument that we should erase 98 percent of people to avoid erasing 2 percent of people is fraught with bizarre and inconsistent logic.

The kind of logic, evidently, that lands you a coveted opinion gig at a legacy newspaper.

The primary question for critics like myself, however, isn’t whether individuals should be able to identify how they want. The question is whether media and academia should keep using the label as a lazy catch-all phrase, downplaying and conflating the contributions of individual cultures.

Because that is exactly what happens when people use the label “Latinx.”

Nobody has pushed back against the label “Latinx” harder and louder than self-identified Chicanos. And for a good reason. Mexican American history runs long and deep in the United States. Chicanos are proud of this history. They are proud of this heritage. As a result, many are defensive and protective of it, particularly when it comes to anything that might erase or gloss over it.

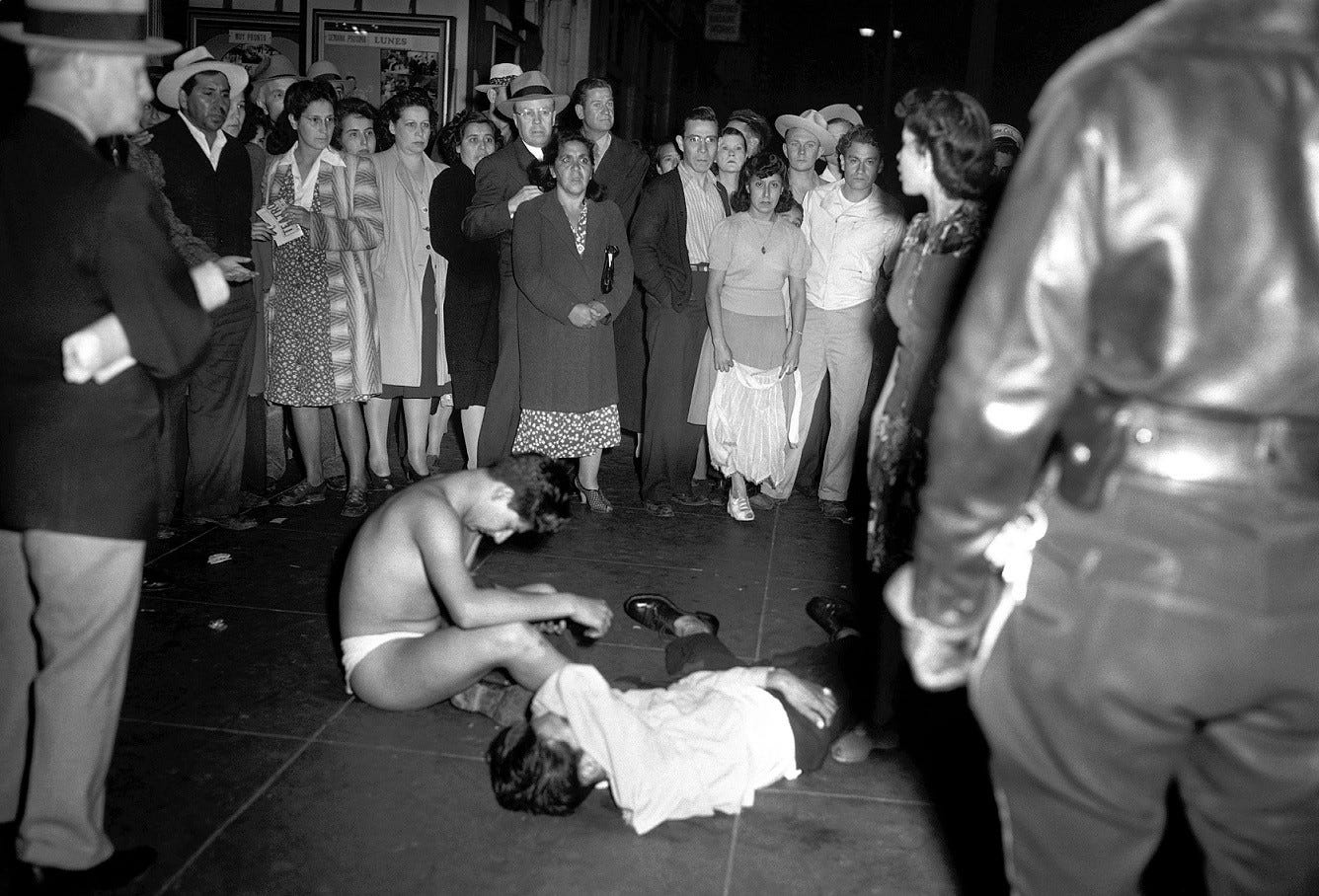

It was, after all, Mexican Americans who fought sailors in the streets of Los Angeles during the Zoot Suit Riots. It was Mexican Americans who were rounded up by the hundreds during World War 2. It was Mexican Americans who marched in the streets of East L.A. during the Vietnam War. It was the Southwestern portion of the United States that once belonged to Mexico.

This is Chicano history, not “Latinx” history.

Nonetheless, this hasn’t stopped some people from suggesting there is a parallel between “Chicano” and “Latinx.” The comparison, however, is flawed. At its heart, “Chicano” is a widely embraced, working class social and political identity. On the contrary, “Latinx” is elitist jargon that the working class largely rejects. It is the polar opposite of “Chicano.” It is the language of the intelligentsia and bourgeoise.

“Latinx” is feelgood psychobabble. “Chicano” is the decades-long culmination of suffering, expression, and rebellion. They aren’t built the same. Pretending otherwise is rhetorical cosplay.

It isn’t surprising that the label “Latinx” continues to stubbornly linger, despite pushback from the very people it pretends to represent. In many cases, the loudest proponents of the label have a political or financial interest in peddling the label (whether they want to openly admit it or not).

For many, the label has nothing to do with inclusion and everything to do with self-preservation. After all, who wants to go through the inconvenience of changing the name of an entire college department, newsletter, or podcast? I don’t blame anyone for protecting their brand. However, it isn’t the fault of the broader Chicano community that a handful of people made the mistake of building their brand on a fleeting sentiment.

The logic is equally self-serving. When proponents argue that there are more important things to debate than “Latinx,” what they are really saying is that 98 percent of people should just shut up and be okay with 2 percent of people imposing their political worldview on them.

What other issues do we apply this same logic to? The argument feels even more disingenuous considering nobody seems to mind debating trivial issues like hot Cheetos and tamales (or is it tamal?).

Other proponents have suggested that embracing our cultural distinctions somehow promotes division. But in a climate ruled by identity politics, how can proponents have it both ways? On one hand, we are told that our intersectional distinctions should inform and dictate our daily mindset. But the moment one of us expresses too much pride in our distinctions, we are told we are being divisive.

Which is it?

Of course, the problem with identity politics is that the politics always trump the identity. In response, many Mexican Americans believe there is a deliberate attempt by special interests to erase their identity in favor of consolidating the Latino community into one generic bloc under the guise of “inclusivity.”

I largely agree. Special interests want us to forget our histories. They want us to believe we can all be summed up with one generic label. But in order to achieve this, they must first pressure everybody to get in line (which turns out is easier said than done when Mexican Americans and self-described Chicanos, who represent the Latino majority, remain the most vocal holdouts).

This isn’t to argue that there can’t be a place for the label. I have a handful of friends, primarily in media and academia (of course), who use the label. Many of them even use the label in the specific context to which it was designed.

However, at this point, the label “Latinx” also comes with bigger political connotations than just being inclusive. By virtue of only a small club of elitist progressives using it, the label now comes pre-baked with a whole set of political ideals and positions that the greater Chicano community may or may not endorse.

And that’s the problem. Latinos are not monolithic. Yet a small group of narcissists want to treat it like it is to serve themselves.

Make no mistake. The debate is bigger than the Chicano identity. It is about media and academia continually steamrolling the working class. It is about elitists trying to convince Chicanos that anyone who refuses to get in line is somehow being “divisive.” But the truth is Mexican Americans, along with self-identified Chicanos, aren’t against inclusivity and tolerance. They are against revisionism, elitism, and erasure.

There is a difference.

JOIN TODAY & Get 10% Off A Daily Chela Insider Subscription For A Year!

Subscribers Get Exclusive News, Videos & Stories:

Our mission is to provide a platform for Mexican Americans, and cover news with the depth and context it deserves.

Here’s how you can help:

Make a Small Monthly Contribution: Your financial support will help us cover operational costs, pay our dedicated team, and expand our reach to more readers.

How To Support:

To subscribe, click on the button below. Thank you for your support and for believing in the power of independent media. Together, we can make sure that every voice is heard and every story is told.